99 Problems and Data is One

11 minute read

In the first post I introduced my PhD project on predicting reaction conditions - the specific parameters like temperature, pressure, and chemical additives needed to make chemical reactions work efficiently. This time we are going to look at one reason why predicting reaction conditions is really HARD. Especially using the data-driven approaches that are all the rage nowadays.

Introduction

That one reason is data. Recently, the 2024 Nobel Prize in Chemistry was given to David Baker, Sir Demis Hassabis and John M. Jumper ‘for computational protein design’ and ‘for protein structure prediction’ respectively. With machine learning approaches showing so much success in the structural biology world, some of you may be wondering why similar models don’t exist for predicting reaction conditions, or for any scientific problem that you want to solve. The answer to that question is data. Protein structure prediction was made possible by an explosion in the number of high-quality protein structures being deposited in the Protein Data Bank (PDB). Such diverse and high-quality data provide the ideal starting point for building machine learning models, because now many protein sequences map one-to-one to highly accurate protein structures. Of course, the models still needed to be thought of and created in a way which used this data source to its maximum, and the incredible achievements of the 3 aforementioned scientists should not be understated.

However, in chemistry, and particularly chemical synthesis, such a dataset is not yet available. We will discuss the 2 ‘types’ of data source for training ML models for chemical reactions, and we will introduce the 3 main issues associated with them.

Data Sources

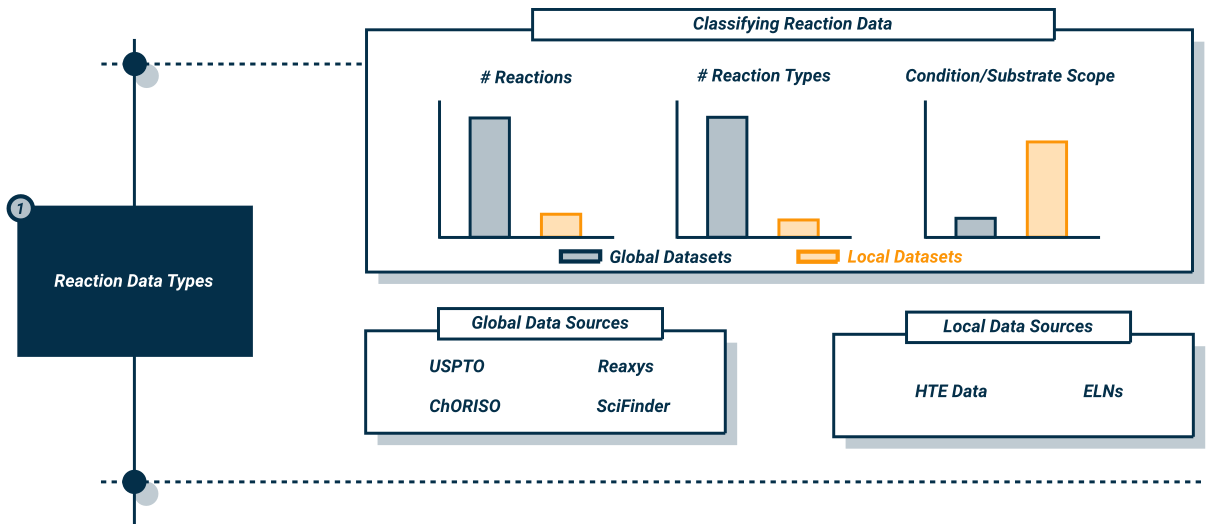

We can break down data sources for chemical reactions into 2 main ‘types’: ‘local’ data sources and ‘global’ data sources.

‘Local’ Data Sources

Think of ‘local’ data sources like a deep dive into a single neighborhood - we know everything about a small area. In chemistry terms, this means databases of chemical reactions which cover a small range of chemical reaction space. These sources typically focus on a single reaction type, and often only use a handful of unique starting materials. However, these data sources are valuable, as they cover a wide range of different conditions for a given set of substrates. Furthermore, these datasets normally arise from High Throughput Experimentation (HTE) projects, often using automated, robotic platforms to carry out the reaction. Therefore, there is typically lower error associated with these data points in comparison to reactions which were carried out by humans.

Examples of such datasets include HTE data and Electronic Lab Notebooks (ELNs) which are records of the chemical reactions carried out in industrial settings. However, ELNs are typically proprietary, meaning that they aren’t available to researchers outside the company that the ELN originated from.

‘Global’ Data Sources

In comparison, ‘global’ data sources cover significantly larger chemical spaces. In the same analogy as above, we ‘zoom out’ to look at the map of an entire country, meaning that the ‘detail’ on specific ‘neighborhoods’ (reaction types) is lower. These ‘global’ datasets cover a wide range of different reactions, substrates and conditions. But crucially, the variety of conditions covered for a single substrate is limited, meaning that learning the relationship between conditions and reactivity for individual substrates is challenging. Of course, these datasets are useful, and are frequently used for the training and benchmarking of yield prediction models, chemical retrosynthesis (predicting how to make given compound) and condition prediction. However, the sources of the data in these large datasets is more questionable than their ‘local’ counterparts. Data often comes from reactions carried out by humans, so naturally there is more error in both the recording of data (missing reagents, reactants and products), as well as the experimental procedure itself. Furthermore, this data is often not curated, having been sourced from text-mining, which is prone to errors too. These factors compound to make the datasets littered with mistakes and errorneous entries which hinder the development of ML models and data-driven analysis.

Sources for this data include the US Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO), Reaxys and Scifinder. From these, only the USPTO data is freely available without payment.

| Global Datasets | Local Datasets |

|---|---|

| USPTO | HTE data |

| Reaxys | ELNs |

| Scifinder | |

| ORD | |

| Pistachio |

bold = publically available.

|

|---|

| Different types of data sources and their properties. Figure inspired by this paper which gives a great overview on data for reactivity modelling. |

Data Problems

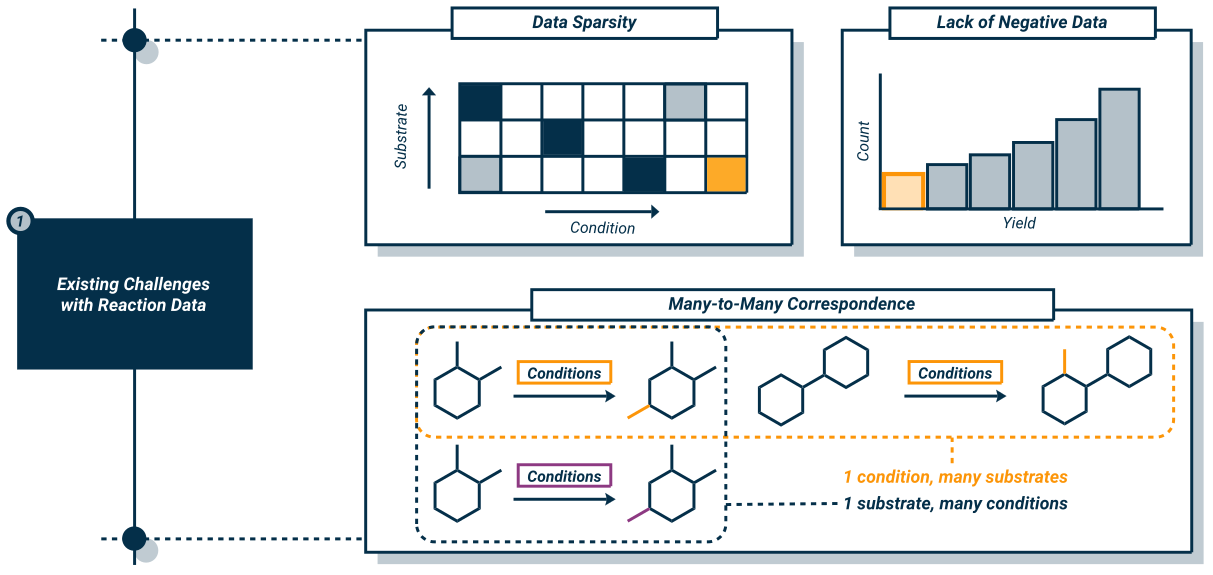

With an understanding of the sources and nature of the data that they contain we can begin to concentrate in more detail on the challenges faced when using these data sources. We can broadly classify these challenges into 3 categories which we will explain and look at the downstream impact when modelling:

- Data sparsity

- Many-to-many relationships between conditions and reactions

- A lack of negative data

Data Sparsity

We begin with a problem briefly touched on above. Chemical reaction data is massive, for any given reaction and substrates, we can use a huge amount of potentially valid conditions to get our desired product. However, the reality is that most of these conditions are never explored. If we have some conditions that work for our reaction, why should we waste time, effort and money exploring more reaction space to achieve small improvements in yield. As a result, our datasets end up being sparse, where reactions typically have no more than a couple (and normally one) set of conditions associated with it. This has big implications for downstream condition prediction, since we have very limited exploration of ‘condition space’ for substrates meaning that models can’t learn the intricate relationships between the substrate (specifically its reactivity) and the conditions. This problem is improved on in HTE data, where a much larger number of conditions are screened and recorded, leading to strong performance in condition prediction and optimisation. However, for global datasets, this is an issue which has yet to be resolved, and requires a concerted effort to produce and record data for a wide variety of different reactions.

Many-to-Many Relationships Between Reactions and Conditions

This challenge is unavoidable with reaction data, and directly ties into the previous section. Reactions can proceed under a number of different conditions. Similarly, a single set of conditions may be applicable to a wide number of substrates. Issues arise due to the complex relationship between both the conditions and the reactions. Minor changes in conditions can lead to significantly different outcomes which was discussed in the first blog. This feature makes evaluating condition prediction tools challenging. For example, a model might predict a set of conditions for a given reaction which do not match the ground truth, however, this set of conditions may work in reality but was simply never tested (see the section above). Therefore, we have large amount of unlabelled positive data, making evaluation of these tools without going to a lab bench very difficult.

Lack of Negative Data

This is very closely related to the data sparsity problem. Simply put, there are minimal amounts of recorded reactions which don’t work. When training ML models, it is important to have a balanced dataset which ideally covers a wide range of substrates, and a wide range of conditions for that substrate. Understanding conditions which don’t work is just as important as understand those which do. Particularly if the conditions which don’t work, can be used for other substrates, as this gives crucial information about the underlying reactivity. However, often researchers don’t publish negative data (because until recently, people were not as interested in what didn’t work, and therefore it may have been considered pointless). HTE data offers an improvement once again, since this data frequently includes examples of reactions which don’t work. Like the first point, a global effort to produce consistent reaction records and to record ALL reactions is required to mitigate this challenge, and initiatives such as the Open Reaction Database represent strong steps in this direction. However, this challenge can also be mitigated without additional new data. Researchers can enhance datasets using ‘synthetic’ data. This is reaction data which doesn’t correspond to reaction that have actually been performed, but we can generate with certainty knowing that they would happen. For example, take a reaction A -> B under conditions C. If this reaction occurs with 100% yield, we know that no other products apart from B can be produced. Therefore, we can augment our dataset with examples of A -> D under conditions C which we label as negative. Other augmentation methods exist in an attempt to solve the ‘imbalanced’ dataset problem.

|

|---|

| A pictorial depiction of the 3 main problems with chemical reaction data. 1. Data Sparsity: For each reaction in a database, the number of conditions explored per reaction is very low. 2. Many-to-Many Correspondence between reactions and conditions: Reactions can proceed under many conditions (many of which aren’t explored). Similarly, the same conditions can be applied to lots of different reactions successfully. 3. Lack of Negative Data: Most reaction datasets are ‘unbalanced’ mainly favouring successfully reactions. To develop models of chemical reactivity it is also important to understand which reactions don’t work so models can better understand the links between chemical reactivity and the required conditions. |

Conclusion

I could go on about data challenges for chemical reactions for much longer, but I am sure that no one wants that. I hope that you found this an interesting introduction to the challenges that we face when building models of chemical reactivity.

We’ve discussed the different issues with data when modelling of chemical reaction: data sparsity, many-to-many relationships, and lack of negative data. Whilst these might seem like insurmountable obstacles in our quest to predict reaction conditions. The chemistry community is actively working to address these challenges through several promising approaches:

- Data Collection Initiatives: Projects like the Open Reaction Database are encouraging chemists to share both successful and failed reaction attempts, gradually building a more comprehensive picture of chemical reactivity.

- Automated Chemistry: High-throughput experimentation platforms are systematically exploring reaction spaces, generating the kind of dense, high-quality data that machine learning models need.

- Novel Modeling Approaches: Researchers are developing innovative ways to work with sparse data, such as:

- Transfer learning from related chemical problems

- Using chemical knowledge to generate synthetic negative examples

- Combining machine learning with fundamental chemical principles

Looking ahead, we’re likely to see a hybrid approach emerge - one that combines data-driven methods with chemical theory and automated experimentation. While we may not have an “AlphaCondition” yet, we’re making steady progress toward more reliable prediction of reaction conditions.

For those that are interested in learning more, there is a fantastic paper on this topic linked here:

and some others which also discuss this: